Is Cherry a Tropical Fruit? No

Cherries are not considered tropical fruits; they are classified as temperate fruits because they require a cold period to flower and produce fruit.

Tropical fruits are those that are native to the tropical regions of the world, where the climate is warm and frost-free year-round. These include fruits like mangoes, pineapples, and papayas.

Cherries, on the other hand, belong to the genus Prunus and are better adapted to temperate regions. They need a certain amount of cold weather, known as chill hours, to properly bloom and set fruit.

Cherries thrive in colder climates, requiring chill hours for optimal fruit production, unlike true tropical fruits.

Key Takeaway

2 Fruit Types: Is Cherry a Tropical Fruit

| Fruit Type | Climate Requirement | Chill Hours | Origin | Example Fruits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tropical Fruits | Warm, frost-free | Not required | Tropics | Mango, Pineapple, Papaya |

| Temperate Fruits | Cold winters | Required | Temperate zones | Cherry, Apple, Pear |

Defining Tropical Fruits

Tropical fruits are typically those cultivated and thrived within the equatorial belt, characterized by their necessity for warm climates and no frost conditions for optimal growth.

These fruits, often rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, exhibit a broad genetic diversity, resulting in a wide range of flavors, colors, and forms.

The term ‘tropical fruit’ is not solely horticultural, but also geographical and climatic, delineating the specific environmental requisites for their propagation.

Horticulturalists categorize them based on their inability to withstand cold temperatures, a factor which significantly influences their geographical distribution.

The cultivation of these fruits is predominantly in regions that experience a consistent climate year-round, with ample rainfall and high humidity levels, conditions that are quintessential for their successful cultivation and maturation.

Cherry Varieties Examined

Within the genus Prunus, cherry species are broadly categorized into sweet and sour types, each with distinct horticultural traits and uses.

The geographic distribution of cherry varieties reveals regional growth differences, influenced by climate, soil conditions, and agricultural practices.

A review of popular cultivars, such as ‘Bing’ and ‘Montmorency,’ allows for a comparative analysis of their propagation, adaptability, and market relevance.

Sweet Vs Sour

Cherries are broadly categorized into sweet and sour varieties, each with distinct taste profiles and culinary uses.

The sweet cherry, belonging to the species Prunus avium, is typically consumed fresh and is favored for its succulence and high sugar content, making it amenable to desserts and direct snacking.

Sour cherries, on the other hand, are of the species Prunus cerasus and possess a more acidic flavor profile, rendering them ideal for cooking and baking applications where their tartness can be balanced with sweeteners.

Varietal distinctions are not merely gustatory but also extend to horticultural attributes such as tree hardiness and fruit-bearing schedules.

Understanding these differences is crucial for both agricultural cultivation and culinary application, enabling optimized usage of each cherry type.

Regional Growth Differences

The cultivation preferences of cherry varieties reflect their adaptability to temperate climates rather than tropical zones, with specific regions around the world offering ideal conditions for their growth.

Sweet cherries, such as the Bing and Rainier varieties, thrive in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, an area characterized by cold winters and warm summers.

On the other hand, sour cherries, like the Montmorency, are predominantly cultivated in the eastern European regions and the Upper Midwest of the United States, where the climate is more variable, and the winters can be harsher.

These cherries require a period of dormancy provided by colder temperatures, a criterion not met by tropical environments.

Consequently, the geographical distribution of cherry cultivation is heavily influenced by climatic factors, underscoring the fruit’s preference for non-tropical conditions.

Popular Cultivars Identified

Cultivar selection plays a pivotal role in cherry production, with numerous varieties adapted to the specific climate conditions of temperate regions.

Through meticulous agricultural practices and breeding, cultivars have been developed to enhance flavor profiles, increase yield, and improve resistance to diseases.

In the examination of cherry varieties, particular attention is given to:

- Bing: Renowned for their vibrant, deep red hue and profound sweetness, Bing cherries are a commercial standard for fresh market consumption.

- Rainier: Characterized by a distinctive blush on a yellow background, these cherries are prized for their exceptionally sweet and delicate flavor.

- Montmorency: As a sour cherry variety, Montmorency is predominantly utilized in culinary applications, valued for its tartness and firm texture after cooking.

These cultivars represent a fraction of the genetic diversity within Prunus avium and Prunus cerasus species, each with unique attributes catering to specific market demands and agronomic conditions.

Cherry Geographic Origins

Originating in the temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, cherry trees have a history that excludes them from the category of tropical fruits. They are indigenous to areas of Europe, Western Asia, and parts of the Middle East.

Historical evidence suggests that these regions have been cultivating cherries since before recorded history, with their spread being facilitated by birds and humans.

The genus Prunus, to which cherries belong, thrives in climates that experience cold winters and moderate summers, conditions not typically associated with the tropics.

Furthermore, archeological findings indicate domestication events that could date back to the Bronze Age, underscoring the extensive temperate pedigree of these fruit-bearing trees.

This deep-rooted temperate origin is crucial to understanding the environmental conditions cherries require, a topic we will explore in the following section.

Climate Requirements for Cherries

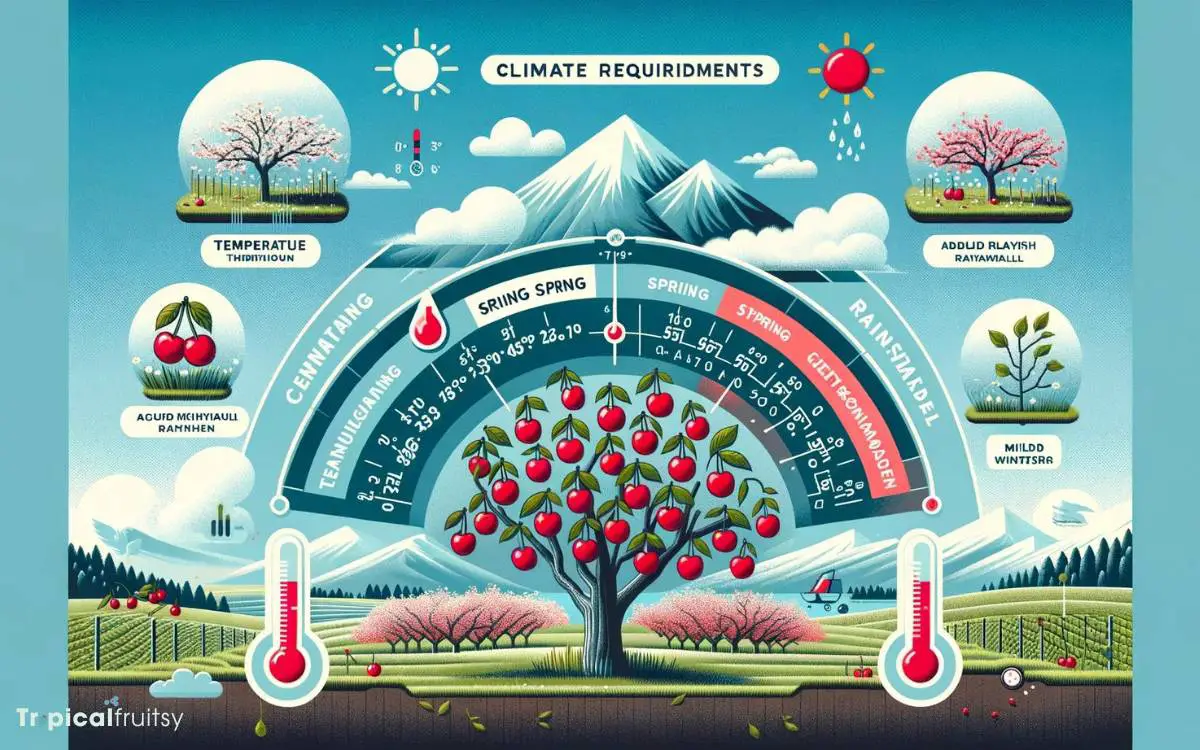

Cherries thrive under specific climatic conditions that are generally non-tropical in nature.

The temperature needs of cherry trees are characterized by a requirement for cold winters to facilitate dormancy and temperate summers to promote optimal fruit development.

Seasonal weather patterns, particularly the incidence of frost during flowering, are critical to the successful cultivation of cherries, necessitating a thorough analysis of regional climate data for potential growers.

Temperature Needs

The successful cultivation of cherry trees typically requires a temperate climate with cold winters and warm, dry summers.

To thrive, these deciduous trees necessitate specific temperature ranges during different stages of their growth cycle:

- Chilling Requirement: A period of winter dormancy with temperatures between 0°C and 7°C (32°F to 45°F) is critical. This period, involving several hundred hours, is essential for breaking dormancy and ensuring proper bud development.

- Spring Temperatures: Moderate temperatures are required during the flowering period to promote pollination and fruit set. Late frosts can be detrimental to the blossoms, potentially decimating the year’s yield.

- Summer Heat: Sufficient warmth throughout the summer, generally between 20°C and 30°C (68°F to 86°F), is necessary for fruit development and ripening.

Each of these temperature ranges plays a pivotal role in the physiological processes that dictate the success of cherry production, underscoring the incompatibility of cherry trees with tropical climates, where such distinct seasonal temperature variations are typically absent.

Seasonal Weather Patterns

Seasonal weather patterns, characterized by four distinct phases, are integral to the successful cultivation of cherry trees, which cannot sustain the constant conditions found in tropical environments.

Their dormancy in winter, the blossoming in spring, fruit development in summer, and preparation for dormancy in autumn are all contingent upon the sequential and contrasting climate conditions.

| Season | Climate Requirement for Cherries |

|---|---|

| Winter | Cold temperatures to induce dormancy |

| Spring | Mild temperatures for blossoming |

| Summer | Warm, dry conditions for fruit development |

| Autumn | Cool temperatures to prepare for dormancy |

Cherries require a period of cold winter weather to break dormancy and a sufficient growing season length free from early frosts to mature properly. These climatic dependencies preclude cherries from thriving in a tropical climate.

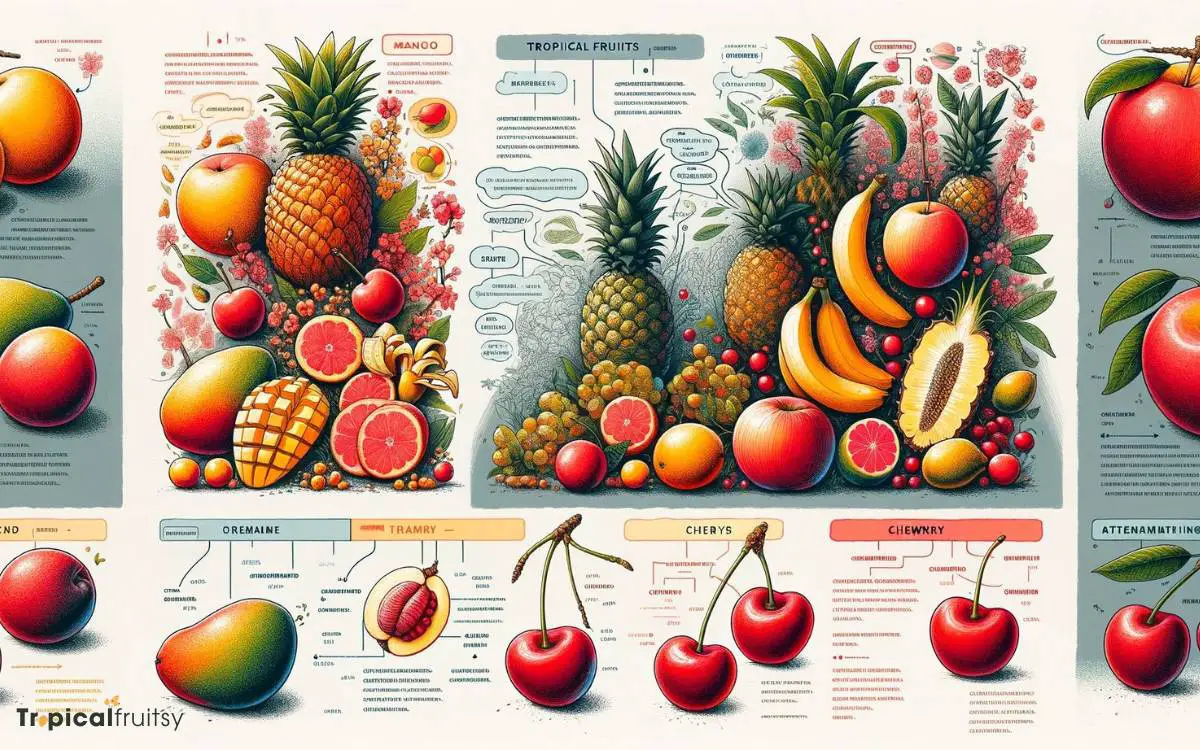

Comparing Cherries With Tropical Fruits

Within the realm of botany, it is crucial to distinguish between cherries, which thrive in temperate climates, and typical tropical fruits that require warmer, more humid conditions.

To elucidate the differences, consider the following:

Climatic Adaptations:

Cherries require a chilling period and are resilient in the face of frost, whereas tropical fruits such as mangoes, bananas, and papayas necessitate year-round warmth and cannot withstand low temperatures.

Growth Patterns:

Cherry trees undergo a dormant winter phase that is absent in tropical fruit trees, which often exhibit continuous growth.

Fruit Characteristics:

The skin and flesh of cherries are typically thicker and firmer, an adaptation to temperate variability, contrasted with the soft, moisture-rich textures of tropical fruits that facilitate rapid nutrient intake in consistently humid environments.

This analytical comparison underscores the fundamental botanic dissimilarities driven by climatic demands.

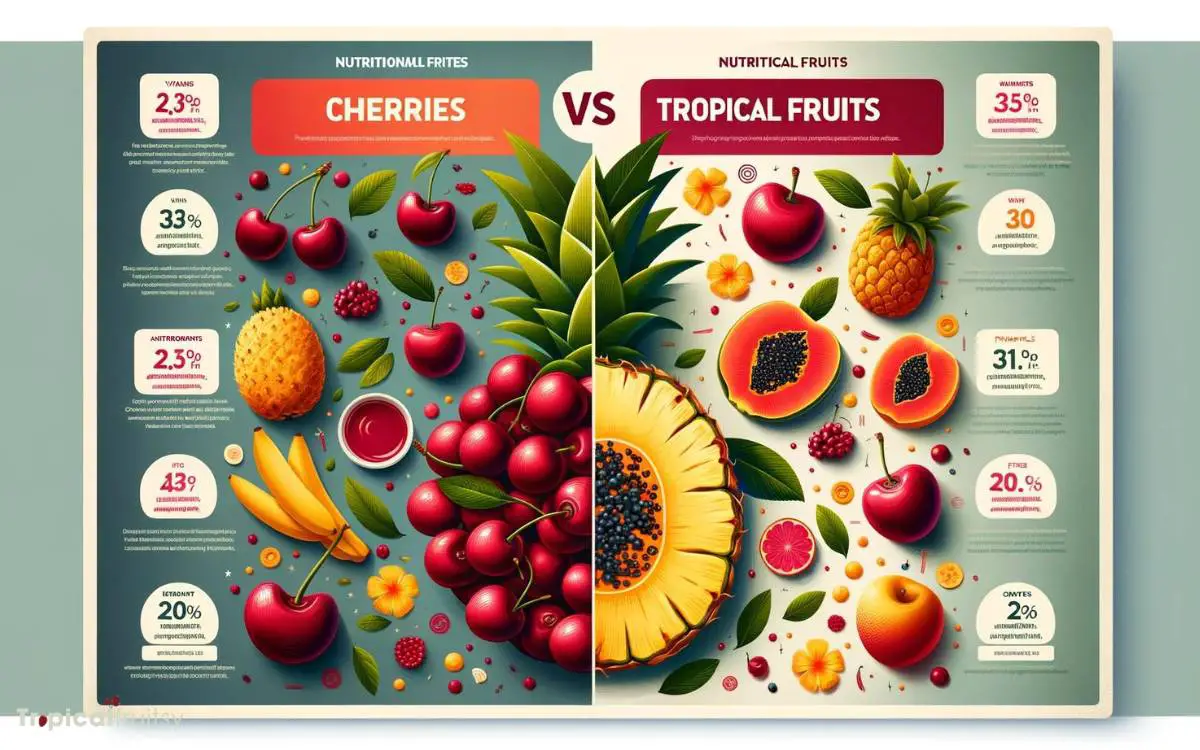

Nutritional Profiles: Cherry Vs. Tropicals

Several nutritional elements differentiate cherries from tropical fruits, including variations in vitamin, mineral, and antioxidant content.

Cherries are particularly known for their high levels of anthocyanins, which are potent antioxidants, while tropical fruits are often rich in vitamins like vitamin C and dietary fibers.

The nutritional profiles of cherries in comparison to typical tropical fruits such as mangoes and pineapples illustrate significant differences in their contributions to a balanced diet.

| Nutrient | Cherries (per 100g) | Tropical Fruits (average per 100g) |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 7 mg | 46.9 mg |

| Dietary Fiber | 2 g | 2.7 g |

| Antioxidants | High (Anthocyanins) | Variable (Vitamin C, Beta-carotene) |

This tabulation underscores that while cherries offer substantial antioxidant properties, tropical fruits generally provide higher vitamin C content and a comparable amount of dietary fiber.

Cherry Cultivation Practices

We must consider the specific horticultural practices employed in growing cherries to understand their classification and how they differ from tropical fruit cultivation.

Cherry trees thrive in temperate climates, contrasting significantly with the warm, humid environments preferred by many tropical fruits.

Key aspects of cherry cultivation include:

- Site Selection: Cherries require well-drained, fertile soils with a neutral pH. They are typically grown in regions with cold winters and warm, dry summers.

- Cold Stratification: Cherry trees need a certain number of chilling hours to break dormancy and ensure proper flowering and fruit set.

- Pest Management: While tropical fruits often deal with a different set of pests, cherry cultivation necessitates vigilant monitoring for pests such as aphids and birds that can decimate crops.

These practices underscore the fundamental differences in the agronomy between cherry and tropical fruit production.

Are Cherries and Peaches Considered Tropical Fruits?

Cherries are not considered tropical fruits. They are grown in temperate regions and have a short season. Peaches, on the other hand, are often mistakenly thought to be tropical fruits because of their juicy, sweet flavor and soft flesh. However, despite this common misconception, a peach not a tropical fruit.

Common Myths About Cherries

One prevalent myth about cherries is that they are categorized as tropical fruits, when in fact they flourish in temperate climates.

This misconception may stem from the vibrant, lush appearance of cherries, which evokes imagery of exotic locales.

However, their cultivation requirements involve specific temperature ranges that are characteristic of non-tropical regions.

Cherries necessitate a period of cold dormancy to trigger bud development, a process incompatible with the constant warmth of the tropics.

Further, the assumption that all brightly colored fruits are inherently tropical is a reductionist view that overlooks the diverse climatic adaptations of fruit-bearing plants.

In essence, the classification of cherries as tropical fruits reflects a superficial assessment and disregards the botanical and ecological nuances that define their growth patterns.

Conclusion

Cherries are temperate fruits, distinct from tropical counterparts in both climatic needs and geographic origins.

Cherries thrive in cooler conditions, unlike tropical fruits which require warm, humid environments. Comparative analysis reveals notable differences in cultivation practices and nutritional profiles.

A noteworthy statistic is that cherry trees can produce up to 7,000 fruits per season, underscoring their prolific nature within appropriate climates. This high yield contributes significantly to their economic and nutritional value globally.