Is Persimmon a Tropical Fruit? Unlocking the Truth!

Persimmons are a subject of intrigue when classifying fruits by climate affinity, and their categorization often prompts the question: is persimmon a tropical fruit?

To demystify this, one must consider the botanical criteria that define tropical fruits, characterized by their growth in warm climates near the equator.

Originating from East Asia, persimmons have adapted to a variety of climates. While they are often associated with temperate zones, certain varieties do thrive in subtropical conditions.

The misconception that persimmons are exclusively tropical may stem from their lush appearance and sweet flavor profile, qualities often attributed to tropical fruits.

This brief exploration will delve into the origins, climate preferences, and varieties of persimmons, offering insights into their cultivation and nutritional parallels with other fruits commonly grown in tropical regions, ultimately clarifying their classification in the fruit hierarchy.

Key Takeaway

Defining Tropical Fruits

Regarding the classification of tropical fruits, it is essential to understand that they are typically grown in regions located between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, where the climate is characterized by consistent warmth and minimal frost.

This geographical demarcation provides the requisite environment for the cultivation of species that demand high humidity, ample sunlight, and a frost-free growing period.

Tropical fruits, thus, can be delineated by their climatological needs rather than solely by their phylogenetic lineage.

These fruits often exhibit attributes such as vibrant colors, distinctive flavors, and nutrient-rich profiles.

The persimmon, while adaptable to a range of climates, may not fit strictly within this category due to its ability to withstand cooler temperatures, prompting further examination into its classification as a tropical fruit.

Persimmon Origins Unveiled

The persimmon (Diospyros spp.), while often associated with East Asian cuisine, has a distribution that transcends typical tropical classifications, with species indigenous to varied climatic zones.

Examination of historical cultivation practices reveals a domestication process that significantly predates modern agricultural expansion, suggesting an ancient integration into human diets.

Furthermore, events such as trade and colonization have facilitated the persimmon’s global dissemination, challenging its singular categorization as a tropical fruit.

Native Growth Regions

Persimmons, characterized by their sweet, honey-like flavor, originate predominantly from regions in East Asia, extending their native habitat from China to Japan and Korea.

The persimmon tree, botanically known as Diospyros kaki, thrives in temperate climates that offer warm summers and mild winters, which are typical of its native East Asian regions.

This deciduous fruit tree has evolved to adapt to these specific climatic conditions, which are not necessarily akin to tropical environments.

| Country | Climate Type | Common Variety |

|---|---|---|

| China | Subtropical | Diospyros kaki |

| Japan | Temperate | Japanese Persimmon |

| Korea | Temperate | Asian Persimmon |

| United States | Variable* | American Persimmon |

Historical Cultivation Practices

Historical evidence indicates that the cultivation of persimmon trees dates back thousands of years in East Asia, where they were first domesticated and grown for their sweet fruit.

The persimmon’s botanical ancestry and regional proliferation are underscored by the following:

- Diospyros kaki, the Asian persimmon, is believed to have originated in China, subsequently spreading to Korea and Japan.

- Ancient texts and agricultural manuscripts delineate persimmon cultivation techniques, reflecting the fruit’s significance in traditional diets.

- Fossil records and carbon dating provide corroborative data for the persimmon’s long-standing presence in prehistoric East Asia.

- Selective breeding practices over centuries have led to the development of numerous cultivars with diverse fruit characteristics, optimizing them for various climatic conditions and taste preferences.

These points collectively illustrate the deep historical roots and sophisticated horticultural evolution of the persimmon tree.

Global Spread Events

How did the persimmon, an East Asian native, establish its presence across the globe?

The introduction of persimmon beyond its indigenous range can be attributed to a series of botanical and agricultural dissemination events.

Meticulous analysis of historical records indicates that the expansion began through trade routes and cultural exchanges.

Horticulturalists played a significant role in this spread, recognizing the fruit’s adaptability to various climates beyond its subtropical origins.

The persimmon’s ability to thrive in temperate zones facilitated its proliferation. Concurrently, migratory patterns contributed to its dispersion, with settlers introducing it to new territories.

The culmination of these events has led to the persimmon’s current global distribution, enabling it to be cultivated in diverse ecological regions.

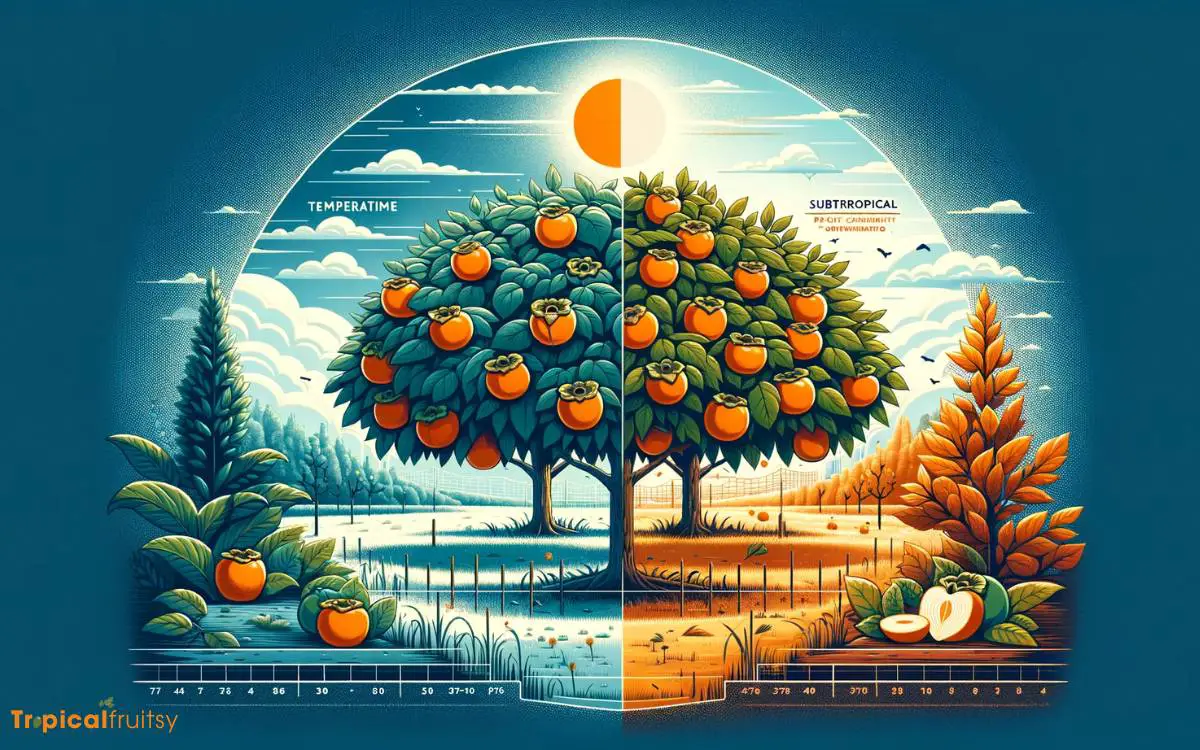

Climate Preferences Explained

Several species of persimmon prefer temperate climates, although a few can thrive in subtropical conditions.

The distinction in climate preference among persimmon species is a result of their varying physiological and ecological adaptations.

To elucidate, consider the following critical climate-related factors influencing persimmon growth:

- Temperature Range: Persimmons demand a range within which they can sustain metabolic processes optimally, usually between 7.5°C and 37.5°C.

- Frost Tolerance: Temperate varieties exhibit a higher resistance to frost, whereas subtropical species may suffer damage.

- Humidity Requirements: Subtropical persimmons necessitate higher ambient humidity for ideal growth.

- Chilling Hours: Some temperate persimmons need a prescribed number of hours below 7.2°C to break dormancy and ensure successful fruiting.

Varieties of Persimmon

Persimmon varieties can be broadly categorized into astringent and non-astringent types, each with distinct ripening characteristics and taste profiles.

Astringent persimmons, such as the ‘Hachiya’, must be fully ripe before consumption to avoid an unpleasantly tannic mouthfeel, whereas non-astringent varieties like ‘Fuyu’ can be eaten while still firm.

An exploration of common cultivars reveals adaptations to diverse climates and consumer preferences, reflecting the fruit’s global cultivation and consumption patterns.

Astringent Vs. Non-Astringent

All persimmon varieties fall into two primary categories: astringent and non-astringent, each with distinct characteristics and ripening processes.

The astringency in persimmons is due to the presence of soluble tannins that diminish as the fruit ripens or after certain treatments.

Here are key differences between the two categories:

- Astringent persimmons must be fully ripe before consumption to avoid an unpleasant, puckering taste.

- Non-astringent persimmons can be eaten while still firm, as they have lower tannin levels even in their unripe state.

- The ripening of astringent varieties can be accelerated by exposure to carbon dioxide or ethanol.

- Non-astringent types are generally more amenable to commercial cultivation due to their immediate edibility.

Understanding the nuances between these categories will enhance our exploration of common cultivars in the subsequent section.

Common Cultivars Explored

Let’s now examine some of the popular persimmon varieties, which showcase the diversity of this fruit beyond its categorization into astringent and non-astringent types.

The ‘Hachiya’ cultivar is widely recognized for its acorn shape and is predominantly astringent until fully ripe.

On the other hand, the ‘Fuyu’ variety presents a squat, tomato-like shape and is non-astringent, offering a sweet flavor even when firm.

The ‘Tanenashi’ persimmon is another astringent type, valued for its conical shape and deep orange hue, often utilized in dried forms.

Conversely, the ‘Jiro’ persimmon, similar to ‘Fuyu’, is non-astringent and can be consumed while still crisp.

Each cultivar possesses distinct ripening characteristics and flavor profiles, catering to a range of palates and culinary applications.

Misconceptions About Persimmons

A common misconception about persimmons is that they are exclusively tropical fruits, when in fact they can also thrive in temperate climates.

This belief may stem from their vivid coloration and sweet flavor profile, which are characteristics often associated with tropical produce.

However, the adaptability of persimmons to a range of environments is underscored by the following points:

- Some varieties, like the American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), are native to regions that experience cold winters.

- Persimmon trees can withstand temperatures as low as -25°C, indicative of their temperate resilience.

- The fruit’s peak season in the northern hemisphere is during the autumn months, not typically associated with tropical climates.

- Successful persimmon cultivation extends into USDA hardiness zones 7 through 10, encompassing non-tropical areas.

Persimmon Cultivation Insights

We must consider various factors when examining the cultivation of persimmons, recognizing that their growth is not limited to tropical climates and involves specific horticultural practices.

Optimal persimmon production necessitates a temperate climate with moderate winters and relatively mild summers; excessive heat or cold can detrimentally affect the fruit’s development.

Soil composition is paramount; well-drained, sandy loam with a neutral to slightly acidic pH is ideal.

Persimmons require adequate water during the growing season, yet they are susceptible to root rot in overly saturated conditions. Cultivators often implement drip irrigation systems to manage moisture levels meticulously.

Pruning is another critical aspect, enhancing sunlight penetration and air circulation within the canopy, which is vital for the prevention of fungal diseases and ensuring fruit quality.

Propagation typically involves grafting to ensure consistency in fruit characteristics, a technique that requires precise execution.

Nutritional Profile Comparison

In addition to horticultural practices, the nutritional profile of persimmons further distinguishes them from typical tropical fruits, offering a unique blend of vitamins, minerals, and fiber.

Persimmons are particularly noted for their high vitamin A content, which is essential for optimal eye health and immune function.

Moreover, they provide a substantial amount of vitamin C, contributing to antioxidant protection and skin health.

To underscore the nutritional attributes of persimmons, consider the following:

- High dietary fiber: Supports digestive health and may aid in cholesterol management.

- Rich in manganese: Necessary for bone development and enzymatic functions.

- Contains flavonoids: These phytochemicals possess anti-inflammatory properties.

- Low in calories: Offers a nutrient-dense option for those monitoring caloric intake.

This analysis illustrates how persimmons bring forth a nutritionally dense profile, deviating from the conventional tropical fruit archetype.

So, Is Persimmon a Tropical Fruit or Not?

Yes, a persimmon is considered a tropical fruit due to its origins in China and Japan, where it grows in warmer climates. However, it’s important to note that a fig is not a tropical fruit, despite its sweet taste and association with warmer regions.

Incorporating Persimmons in Cuisine

While persimmons distinguish themselves nutritionally from typical tropical fruits, they also offer versatility in culinary applications, ranging from sweet desserts to savory dishes.

The two primary varieties, the astringent Hachiya and the non-astringent Fuyu, exhibit differing culinary compatibilities.

Hachiyas, with their gelatinous texture when fully ripe, are predominantly utilized in purees and baked goods, where their inherent sweetness and moisture contribute to the dish’s flavor profile and structural integrity.

Conversely, Fuyus, with their firmer texture, can be sliced for raw consumption in salads, integrated into grain-based sides, or roasted to accompany protein-centric entrées, imparting a subtle sweetness that complements umami-rich components.

Chefs capitalize on persimmons’ unique textural properties and flavor profiles to enhance gastronomic creations.

Conclusion

Persimmons, often enshrouded in misconception, are not quintessential tropical fruits but rather temperate offerings that grace the world with their presence.

While they can masquerade convincingly as tropical brethren, their climatic predilections and origins speak to a versatility that transcends simple geographical categorization.

This chameleon of the fruit world provides a nutritional cornucopia and culminates in a symphony of culinary versatility that is nothing short of a gastronomic ballet.