Is Tomato a Tropical Fruit? No!

Tomatoes are not typically classified as tropical fruits. They originate from the Andean region of South America, which is not considered a tropical climate. However, they can grow in a variety of climate conditions, including tropical regions.

The tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) is a versatile fruit that is often grown in temperate regions but can also thrive in tropical environments.

Here’s why tomatoes are not exclusively tropical:

While tomatoes can grow in the tropics, their adaptability to various climates does not confine them to tropical fruit status.

Key Takeaway

Comparative Analysis: Tomatoes vs. Typical Tropical Fruits

| Characteristics | Tomatoes | Typical Tropical Fruits |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Andean region, South America | Tropical regions (e.g., Central and South America, Southeast Asia) |

| Climate | Temperate to tropical | Predominantly tropical |

| Temperature Range | Can tolerate a wide range, including cooler temperatures | Requires consistently warm temperatures |

| Botanical Classification | Fruit (berry) | Various (e.g., drupes, berries, hesperidium) |

| Growth Habit | Annual | Often perennial |

| Culinary Use | Commonly used as a vegetable | Usually eaten as a fruit or in sweet dishes |

The Tomato’s Botanical Identity

Although commonly regarded as a vegetable in culinary contexts, the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) is botanically classified as a fruit, specifically a berry.

This classification arises from the tomato’s development from the ovary, after the ovule is fertilized, situated at the base of the flower.

Structurally, it exhibits characteristics typical of berries, such as fleshy interiors and embedded seeds.

The confusion in everyday usage stems from the tomato’s savory flavor profile and its culinary applications, which align more closely with vegetables than the sweet profiles expected of fruits.

This misclassification is further entrenched by historical legal precedents, such as the United States Supreme Court decision in 1893.

With this understanding of the tomato’s botanical identity established, the focus now shifts to the origins of the tomato plant, tracing back to its ancestral roots.

Origins of the Tomato Plant

The tomato plant, Solanum lycopersicum, is widely understood to have originated in the western regions of South America, with its native range encompassing present-day Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and the Galápagos Islands.

Archeological and genetic evidence suggests that the process of domestication likely began in Mexico, several millennia ago, where indigenous cultures began cultivating and selecting for larger and more palatable fruit varieties.

The domestication timeline is crucial in comprehending the transformation of the tomato from its wild forms to the diverse cultivars that are integral to global cuisines today.

Native Region

Originating in the western South America and Central America, the tomato plant was first domesticated in Mexico.

The solanaceous genus Lycopersicon, to which the cultivated tomato belongs, is native to the Andean region. Its wild ancestors are thought to have first grown in the coastal deserts of Peru and Ecuador.

| Region | Climate Type | Significance in Tomato History |

|---|---|---|

| Western South America | Tropical and Subtropical | Origin of Wild Ancestors |

| Central America | Varied | Biodiversity and Domestication |

| Mexico | Tropical to Temperate | Site of First Cultivation |

| Peru | Arid to Semi-arid | Habitat of Wild Tomato Species |

| Ecuador | Tropical | Diversity of Wild Relatives |

This native habitat offers a diversity of microclimates, allowing for the evolutionary adaptation of the species.

Understanding the native region is crucial for comprehending the ecological preferences and genetic diversity of tomatoes.

Next, we will explore the domestication timeline, which reveals the transformation of the tomato from a wild plant to a cultivated staple.

Domestication Timeline

Building upon its rich history in South and Central America, the tomato underwent significant changes through domestication. This process began around 500 BC to 700 AD with the indigenous peoples of Mexico.

Archaeobotanical evidence suggests that the process of tomato domestication was gradual and complex. It involved selection for desirable traits such as size, taste, and color.

The earliest domesticated tomatoes were likely small and varied in color, including yellow and purple variants.

As a foundation of Mesoamerican agriculture, the tomato was integrated into a sophisticated system of crop rotation and companion planting.

Over centuries, selective breeding by indigenous cultivators accentuated characteristics that facilitated consumption and cultivation.

These efforts resulted in larger, more palatable fruits that bore a closer resemblance to the tomatoes familiar to us today.

Tomato’s Global Migration

The global dissemination of the tomato from its neotropical origin is a testament to its remarkable adaptability and the human fascination with its culinary potential.

As the tomato spread through trade and colonization, it underwent selective breeding and acclimatization, allowing it to thrive in a wide range of temperate to subtropical environments.

This migration and subsequent adaptation raise questions about the intrinsic characteristics of the tomato that facilitated such widespread cultivation, transcending its tropical beginnings to become a staple in diverse global cuisines.

Origin to Worldwide

Tomatoes, native to western South America, underwent a remarkable global migration following their introduction to Europe by Spanish explorers in the 16th century.

The initial spread of tomatoes can be attributed to the plant’s adaptability and the burgeoning global trade routes.

Europeans, initially wary of the tomato due to its membership in the nightshade family, gradually incorporated it into their cuisine.

From Europe, tomatoes spread to European colonies and trading partners, becoming entrenched in diverse culinary traditions.

Botanists and agriculturists played a role in this migration, selecting varieties that could thrive in various climates.

Consequently, the tomato’s journey from a New World plant to a global staple demonstrates a complex interplay of horticulture, gastronomy, and commerce.

Adaptation Across Climates

While the tomato originated in a specific climatic region, its adaptability has allowed it to thrive in a wide range of environments, reflecting its remarkable global migration.

Through selective breeding and natural variation, tomatoes have developed diverse cultivars with distinct tolerances to temperature, humidity, and soil conditions.

This genetic plasticity is a testament to the species’ evolutionary resilience and has played a pivotal role in its widespread cultivation.

Agriculturists have meticulously optimized tomato strains for varying latitudinal exigencies, thus facilitating its ubiquity across continents.

As a result, the tomato’s journey from its ancestral ground to temperate and even subarctic locales is emblematic of its botanical versatility.

With such a capacity for adaptation, the categorization of the tomato as a tropical fruit becomes a complex discourse, which we will explore next.

Defining a Tropical Fruit

Understanding tropical fruits involves recognizing their common characteristics. These fruits typically grow in warm climates and regions near the equator.

They are cultivated in environments that maintain a high level of humidity and have no marked seasons. These conditions are conducive to their propagation and maturation.

Scientifically, the classification of tropical fruits goes beyond mere geography. It encompasses a botanical criterion that emphasizes particular plant families known for their prevalence in tropical zones.

For instance, fruits belonging to the families Anacardiaceae, such as mangoes, and Musaceae, like bananas, exemplify quintessential tropical species.

Analyzing the essential aspects of tropical fruits reveals their reliance on consistent temperatures.

They require a necessity for uninterrupted growth cycles and a resilience to the intense solar exposure characteristic of equatorial regions.

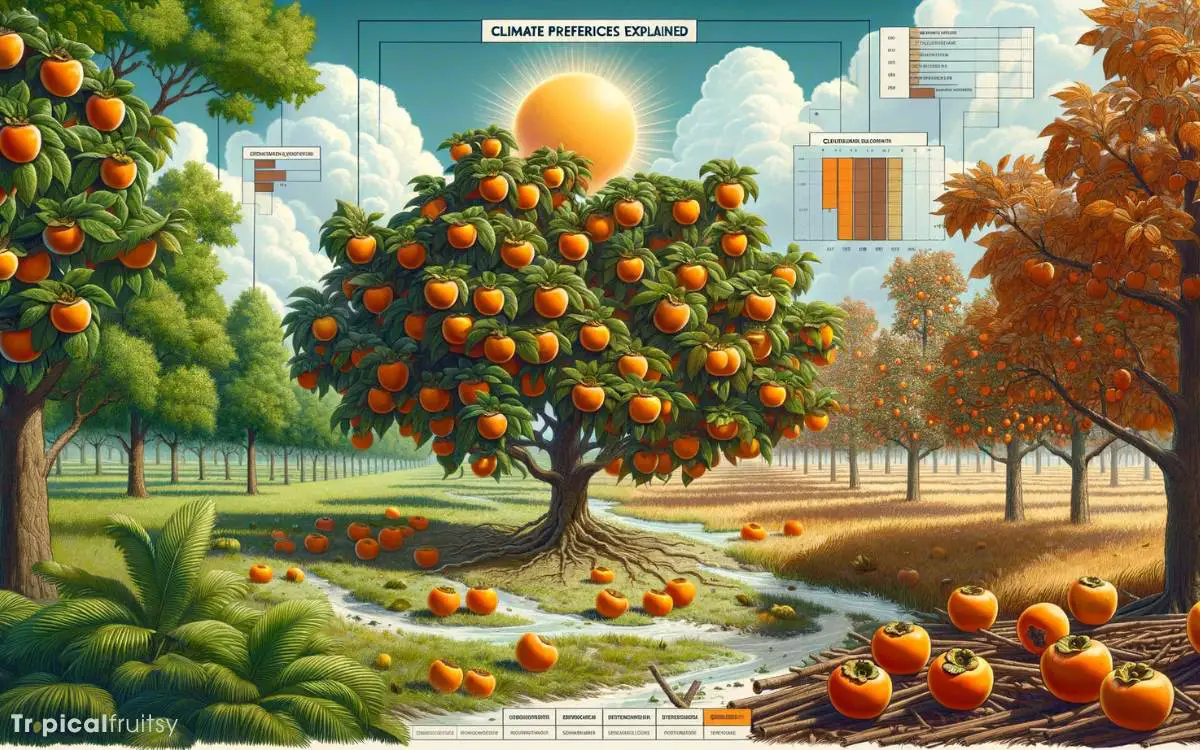

Climate Preferences for Tomatoes

Although tomatoes thrive in warm climates, they do not require the tropical conditions of consistent high humidity and temperature that characterize the growth of traditional tropical fruits.

Optimal tomato cultivation hinges on temperate environments with a clear distinction between day and night temperatures, which facilitate the plant’s developmental processes.

Tomatoes prefer temperatures ranging between 20°C to 30°C during the daytime and 10°C to 20°C at night.

Excessive heat, particularly above 32°C, can impair pollination and fruit set, leading to decreased yields. Conversely, temperatures falling below 10°C can stunt growth and exacerbate vulnerability to diseases.

Therefore, the climate preferences for tomatoes necessitate a balance, ensuring sufficient warmth for growth without the extreme conditions found in tropical zones.

Common Misconceptions

Tomatoes’ classification as non-tropical fruits often contradicts the common misconception that all brightly colored and juicy fruits must originate from tropical climates.

This misapprehension is rooted in a misunderstanding of botanical classification and geographical origins.

Summarizing the misconceptions, realities, and implications related to the origin, color, and juiciness of fruits:

| Misconception | Reality | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Tomatoes are tropical fruits. | Originating in the Andes, tomatoes grow in temperate zones. | Tomatoes adapt well to various climates. |

| Only tropical fruits are vibrantly colored. | Pigmentation results from compounds like lycopene and is not exclusive to tropical fruits. | Vibrant coloration is a poor indicator of climatic origin. |

| Juiciness indicates a tropical origin. | Water content is more closely related to plant physiology than climate. | Many non-tropical fruits can be equally juicy. |

The examination of these misconceptions paves the way for a deeper appreciation of tomatoes’ versatility, setting the stage for a discussion on their culinary uses worldwide.

Culinary Uses Worldwide

Throughout history, the tomato has been integrated into diverse culinary traditions around the globe, reflecting its versatility and widespread appeal.

This scarlet fruit, with its balance of sweetness and acidity, has been adeptly employed in an array of gastronomic contexts.

From the raw, diced tomatoes in Mexican salsa to the rich, reduced sauces of Italian cuisine, the tomato has proven indispensable.

| Region | Dish | Tomato Use |

|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean | Gazpacho | Raw, blended |

| South Asia | Curry | Pureed, spiced |

| North America | Tomato Soup | Cooked, creamed |

In a scholarly examination, one observes that the culinary applications of tomatoes are as varied as their cultivars.

This universality ignites a debate on taxonomy and culinary classification, seamlessly leading into the subsequent discourse on the ‘tomato: fruit or vegetable debate’.

Are there any other commonly mistaken fruits that are not actually tropical?

Yes, there are other commonly mistaken fruits that are not actually tropical. For example, watermelon is often perceived as a tropical fruit due to its popularity in warm climates. However, watermelon is actually native to the Kalahari Desert in Africa, making it a non-tropical fruit.

Tomato: Fruit or Vegetable Debate

Commonly, the classification of the tomato sparks discussion as to whether it should be considered a fruit or a vegetable, a distinction that hinges on botanical versus culinary perspectives.

Botanically, tomatoes are fruits because they develop from the ovary in the base of the flower and contain the seeds of the plant.

However, from a culinary standpoint, tomatoes are often categorized as vegetables due to their savory flavor profile and usage in dishes.

This dichotomy reflects the complex interplay between scientific classification and cultural dietary practices.

Botanical classification:

- Fruit: Develops from the flower’s ovary; contains seeds.

- Tomato: Meets these criteria; hence botanically a fruit.

Culinary usage:

- Vegetable: Commonly used in savory meals.

- Tomato: Employed as a vegetable in cooking.

Legal and tax implications:

- Tariff codes: May differ based on classification.

- Tomato: Historically subject to vegetable tariffs in certain jurisdictions.

Conclusion

The tomato stands as a botanical enigma, rooted in the warm soils of its native South America, yet flourishing worldwide beyond tropical confines.

This culinary chameleon, often cloaked in the guise of a vegetable, is botanically a fruit, and its journey across continents symbolizes the cross-pollination of cultures.

The academic discourse on its identity reflects the complex interplay of taxonomy, agriculture, and gastronomy, enriching our understanding of global horticultural heritage.