What Part of Ackee Is Poisonous? Find Out!

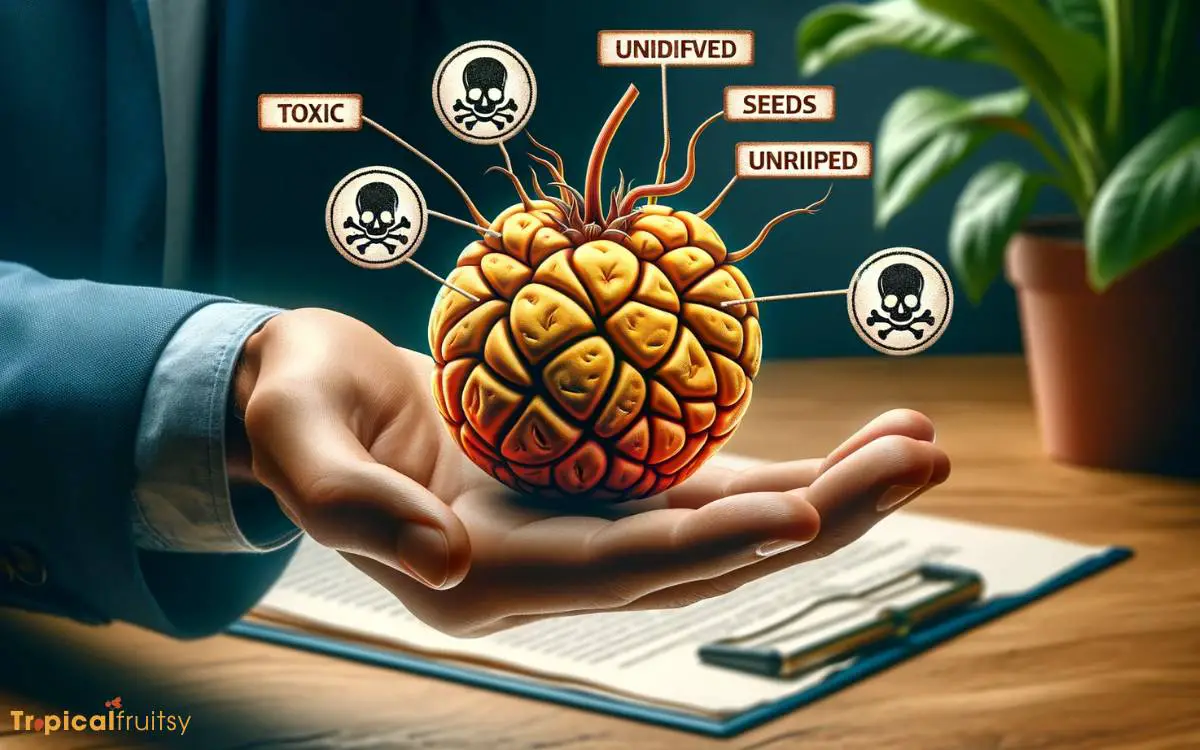

The poisonous parts of the ackee fruit are the seeds, the unripe fruit, and the rind. These contain hypoglycin A, a toxin that can cause Jamaican Vomiting Sickness.

Ackee fruit toxicity is a concern due to hypoglycin A, which can cause severe illness.

The edible part is the ripe aril, while the following parts are toxic:

Consuming these can lead to serious health implications, and proper preparation is essential.

Recognize and avoid the toxic components of ackee to enjoy its unique flavor without health risks.

Key Takeaway

Ackee Fruit Toxicity: Edible Parts & Hypoglycin A

| Edible Parts | Toxic Parts | Toxin Present | Condition Caused |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ripe arils | Unripe ackee | Hypoglycin A | Jamaican Vomiting Sickness |

| Seeds | Hypoglycin A | Jamaican Vomiting Sickness | |

| Rind/Membrane | Hypoglycin A | Jamaican Vomiting Sickness |

The Ackee Fruit Explained

The toxicity of the ackee fruit, a staple in Caribbean cuisine, resides specifically in its unripe arils and seeds.

This toxicity is primarily due to the presence of hypoglycin A, a naturally occurring amino acid that can induce severe metabolic disturbances when ingested.

In its immature state, the concentration of hypoglycin A is significantly higher, posing a risk of hypoglycemia and a potentially fatal condition known as Jamaican vomiting sickness.

Ackee must therefore be harvested when fully ripe, ensuring that the protective pods naturally open, signaling a reduction in hypoglycin A levels to a safer threshold.

The edible portion, the arillar yellow flesh, is then meticulously separated from the seeds and any remaining unripe parts to mitigate any risk of toxicity.

Identifying the Toxic Parts

The toxicological profile of ackee centers on two primary components: the unripe arilli and the seeds. Consumption of the unripe fruit exposes individuals to hypoglycin A, a phytochemical that can induce severe metabolic disturbances.

In parallel, the seeds contain concentrated amounts of toxic compounds, which remain hazardous regardless of the fruit’s maturation state.

Unripe Fruit Danger

Within the ackee fruit, the unripe arils and seeds contain high levels of the toxic substance hypoglycin A, posing serious health risks if ingested.

Hypoglycin A is a naturally occurring amino acid which, upon consumption, can induce a severe condition known as Jamaican vomiting sickness (JVS).

This condition arises from the hypoglycin A’s interference with the body’s ability to metabolize fatty acids and glucose, leading to acute hypoglycemia, vomiting, and even fatal outcomes if not promptly treated.

It is imperative to differentiate between the ripe and unripe states of ackee fruit. The ripe fruit, recognized by its naturally split open pods, reveals non-toxic, edible arils.

Conversely, the unripe fruit, which remains closed, must be strictly avoided due to the concentrated presence of hypoglycin A within its closed arils and seeds.

Toxic Seed Compounds

Every seed of the ackee fruit contains dangerous levels of hypoglycin B, another toxic compound that persists even when the fruit is ripe.

This compound is a type of amino acid that can induce hypoglycemia by inhibiting the body’s ability to produce glucose.

The seeds are therefore recognized as a biohazard, necessitating strict adherence to culinary protocols that ensure their complete removal and disposal.

Analytical methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are used to quantify the concentration of hypoglycin B within the seeds, providing a metric for assessing potential toxicity.

Moreover, these seeds must be handled with caution to prevent contamination of the edible fruit portions.

Understanding Hypoglycin A

Hypoglycin A is a naturally occurring amino acid found in the unripe fruit of the ackee plant, Blighia sapida. It is known to induce hypoglycemia by inhibiting the body’s ability to release glucose into the bloodstream.

The toxicity of this compound is heightened when the ackee fruit is consumed in its unripe state. This can lead to severe health implications such as Jamaican vomiting sickness.

Establishing safe consumption levels requires thorough processing to ensure the reduction of Hypoglycin A to non-toxic concentrations.

Hypoglycin a Toxicity

How does hypoglycin A induce toxicity in humans when consuming unripe ackee fruit?

Hypoglycin A, a naturally occurring amino acid derivative found in unripe ackee, is metabolized within the human body to form methylenecyclopropyl acetic acid (MCPA).

MCPA disrupts fatty acid oxidation by irreversibly inhibiting several dehydrogenase enzymes in the mitochondrial matrix, critical for the normal beta-oxidation of fatty acids.

This inhibition leads to a reduction in the production of acetyl-CoA, pivotal for the Krebs cycle, and diminishes ATP generation. Concurrently, MCPA’s interference with gluconeogenesis results in profound hypoglycemia.

Accumulation of toxic metabolites, like MCPA-CoA, further exacerbates cellular toxicity, leading to a spectrum of clinical manifestations, most notably Jamaican vomiting sickness.

Hence, the consumption of unripe ackee fruit, rich in hypoglycin A, poses serious health risks.

Unripe Ackee Danger

Ingesting unripe ackee fruit exposes individuals to the dangers of hypoglycin A, a compound that can induce severe metabolic disturbances.

Hypoglycin A is notably present in higher concentrations in unripe ackee fruits and can precipitate a state of acute toxic hypoglycemia, known as Jamaican Vomiting Sickness.

| Component | Concentration in Unripe Ackee | Health Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycin A | High | Hypoglycemia, Vomiting |

| Glucose | Decreased Utilization | Energy Depletion |

| Amino Acids | Altered Metabolism | Nutritional Deficiencies |

| Fatty Acids | Accumulation in Liver | Hepatotoxicity |

| Insulin Regulation | Impairment | Metabolic Dysfunction |

The toxicological mechanism involves the inhibition of medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, disrupting fatty acid oxidation and amino acid metabolism.

This biochemical interference results in the rapid depletion of glucose and the accumulation of harmful metabolites within the liver and bloodstream. Understanding the specific thresholds of hypoglycin A toxicity is critical for ensuring safety.

Moving forward, the discussion shifts to pinpointing ‘safe consumption levels’ to mitigate the risks associated with ackee consumption.

Safe Consumption Levels

Determining the threshold at which hypoglycin A becomes toxic is essential for establishing safe consumption levels of ackee.

Hypoglycin A, a naturally occurring amino acid, exhibits toxicity by inhibiting the degradation of fatty acids and amino acids, leading to hypoglycemia and metabolic derangement, notably in cases of Jamaican Vomiting Sickness.

Analytical techniques, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), are employed to quantify hypoglycin A content in ackee fruit.

The established safe limit for hypoglycin A in the edible arilli of ackee is less than 100 parts per million (ppm).

Consuming fully ripened ackee, where the arilli naturally exhibit reduced levels of hypoglycin A, is critical. Adherence to regulatory standards and culinary guidelines is imperative for mitigating the risks associated with hypoglycin A intake.

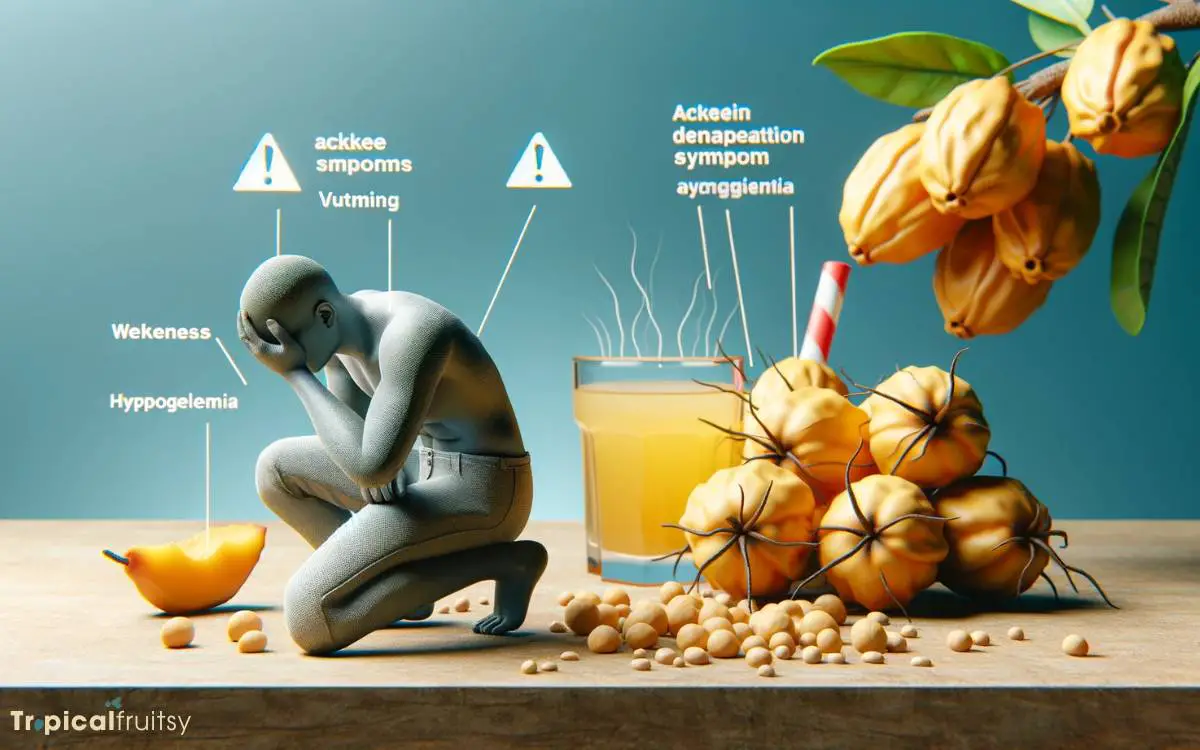

Symptoms of Ackee Poisoning

Several symptoms of ackee poisoning, including vomiting, hypoglycemia, and seizures, can manifest within hours of consuming the unripe fruit or its toxic components.

The severity of these symptoms can range from mild to life-threatening, necessitating a keen awareness of their clinical presentation.

Notably, the following symptoms are commonly associated with ackee poisoning:

- Gastrointestinal distress, characterized by abdominal pain and vomiting.

- Hypoglycemia, which may present as fatigue, dizziness, and even loss of consciousness.

- Neurological disturbances, such as seizures or generalized weakness.

- Cardiovascular instability, potentially leading to fatal outcomes if not promptly addressed.

Understanding the risks associated with ackee consumption is essential. This knowledge segues into the imperative topic of safe preparation practices to prevent such adverse health effects.

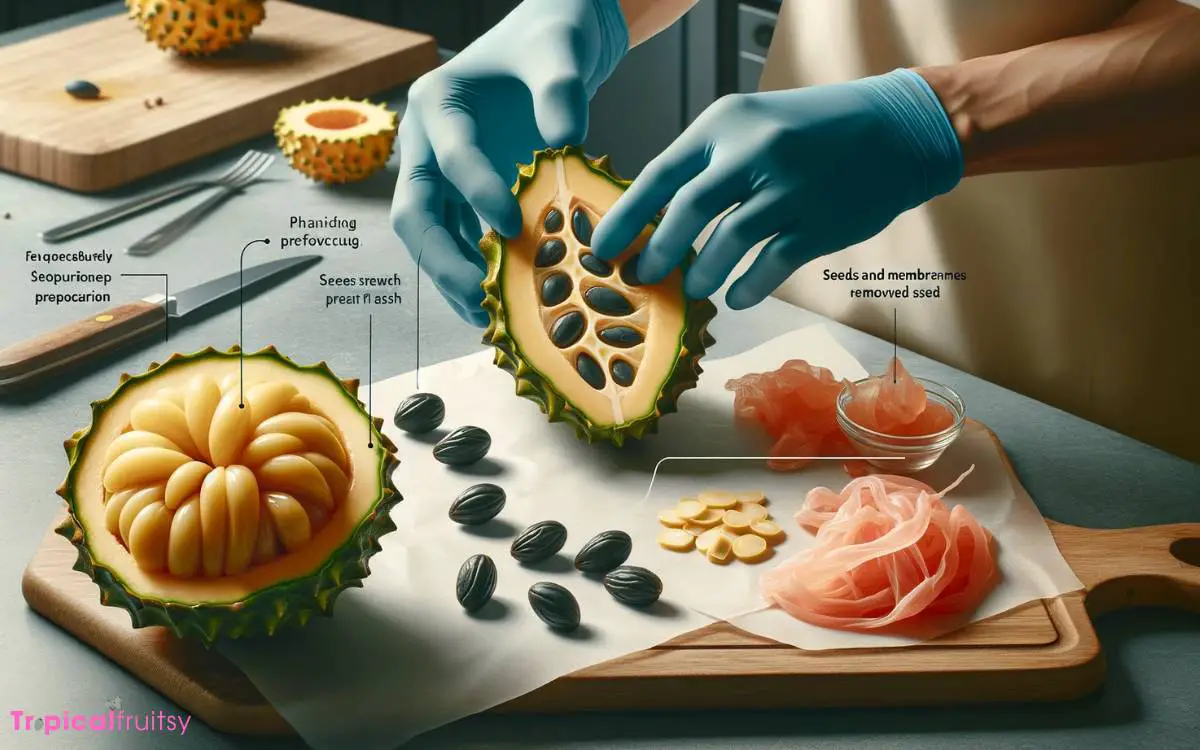

Safe Preparation Practices

To mitigate the risks of ackee poisoning, it is crucial to adhere strictly to established safe preparation practices.

Only fully ripe ackee fruits should be selected for consumption, which are identified by their natural splitting of the pods.

Upon splitting, the arils must be carefully extracted, ensuring that none of the toxic seeds or the pink membrane lining come into contact with the edible portions.

The arils should then be thoroughly cleaned and boiled for at least 30 minutes to inactivate any remaining hypoglycin A.

The water used for boiling must be discarded and never reused. Meticulous adherence to these guidelines significantly reduces the potential for toxic exposure.

This attention to detail extends to understanding the role of ripeness, which is the next critical factor in the prevention of ackee poisoning.

The Role of Ripeness

While the safe preparation of ackee is essential, the ripeness of the fruit is a critical determinant of its safety for consumption, as immature ackee contains dangerously high levels of hypoglycin A.

The role of ripeness can be delineated as follows:

- Toxin Reduction: As ackee ripens, the concentration of hypoglycin A decreases significantly, rendering the arils safe to eat.

- Visual Indicators: Fully ripe ackee fruits naturally split open, revealing the edible arils inside. This visual cue is a reliable indicator of reduced toxicity.

- Harvesting Protocol: Unripe ackee should never be forcibly opened, as this suggests that the hypoglycin A content is still at a hazardous level.

- Regulatory Standards: Many countries have established strict regulations that only allow the sale and consumption of ackee once it has reached full ripeness, to ensure public safety.

How Can I Safely Handle and Prepare Ackee to Avoid Poisoning?

Ackee legality in the US is important to understand when handling this fruit. To safely prepare ackee and avoid poisoning, only consume the ripe, unopened pods. Be sure to remove the toxic parts, wash the fruit thoroughly, and cook it properly before consumption.

Medical Response to Poisoning

In cases of ackee poisoning, immediate medical intervention is paramount to counteract the effects of ingested hypoglycin A.

The clinical approach necessitates an initial assessment to confirm hypoglycin A toxicity, followed by prompt stabilization of the patient’s vital signs.

Intravenous glucose administration is imperative to rectify hypoglycemia. Continuous monitoring of blood glucose levels is essential to prevent rebound hypoglycemia.

In severe cases, supportive measures such as mechanical ventilation may be necessary due to respiratory compromise.

Hemodialysis can be considered to enhance the elimination of the toxin if renal function is intact. The medical team must maintain a high index of suspicion for complications, including hepatic encephalopathy, and initiate appropriate interventions.

Prognosis depends on the timeliness and adequacy of the medical response.

Conclusion

Ackee, while being a culturally significant fruit, harbors potential dangers due to the presence of hypoglycin A, primarily in its unripe arils and seeds. Proper culinary processing and consumption of fully ripe ackee ensure safety.

Despite this, ackee poisoning remains a health concern, with one study revealing that it accounts for 35% of all cases of severe vomiting in Jamaica, underscoring the importance of public education on the safe handling and preparation of this unique fruit.